Reminder on the four rules of firearms safety:

Always treat a firearm as if it’s loaded.

Don’t point your firearm at anything you don’t want to shoot.

Don’t put your finger on the trigger until you’re ready to shoot.

Know your target and what is beyond it.

I thought I’d share the path that led me to long-range marksmanship, and how much you can learn by mastering a gas gun, such as an Armalite (AR) rifle.

Long before I purchased my Tikka and began pursuing 1,000+ yard accuracy, I realized that I had a lot of room to grow with my first rifle, a Palmetto State Armory 16-inch Freedom Rifle.

I built this rifle in 2020 when one of my best friends introduced me to the exciting world of homebuilding. Palmetto State Armory is known for bringing down the cost of owning a reliable, but no-frills, semi-auto rifle.

PSA’s Freedom Rifles won’t deliver the smallest groups, they aren’t the lightest, they won’t hold up as well to abuse, and they don’t come standard with nice-to-have features, such as ambidextrous-safeties. That being said, I’ve found that with regular cleaning and lubing they are quite reliable and accurate-enough for getting started.

After building our rifles, my buddy and I started learning close-range marksmanship and shot some 2-gun competitions with stages out to 100 yards. And at those distances I did ok — I quickly got to the place where I get quick, repeatable “A-Zone” hits from an off-hand stance out to 50 yards, and with a hasty-sling and ideally a kneeling stance or barricade to steady myself, take shots out to 100-yards and beyond.

But I got the sense I wasn’t really stretching this rifle out to its full potential.

My inexpensive, PSA isn’t close to sub-MOA (minute of angle). It’s not a precision rifle or even close to a “DMR” build (Designated Marksman Rifle, the military’s intermediary capability between the basic M4 and a sniper or precision rifle).

But again, I knew I wasn’t close to shooting beyond my platform’s capabilities, and I quickly learned that I should be capable of shooting reliably much further. After all, the U.S. Marines qualify out to 400 yards with iron sights.

I had only excuses.

So I started seeking instruction, literature, and ranges where I could take my rifle beyond what most people assume is the typical range of an AR-15.

There are three things I learned that helped me master basic rifle marksmanship and set me on a course to pursue precision long-range shooting. Hopefully what follows will encourage someone else to pick up their rifle more often and get some range time at 100-yard+ distances.

Learn the Fundamentals of Marksmanship

They’re called the fundamentals for a reason. If you don’t know how to get into a solid stance, hold the rifle appropriately, control your breathing, and properly squeeze the trigger (among other skills), you’re not going to have much fun at longer distances.

Taking my PSA out to the range at 100, 200, and then 500 yards gave me a chance to progressively eat humble pie and address my shortcomings.

For instance, you don’t realize how unstable your stance is until you’ve tried to merely keep a reticle on a 12-inch plate at 200 yards.

You don’t realize how much your breathing can throw a shot until you’ve tried tightening your groups at at 500 and 600-yards while breathing at a “normal” pace.

Fortunately, at distances of up to 200-300 yards you will have minimal impacts from wind (especially when using quality loads, see below), so it’s not hard to isolate to the fundamentals and identify and address your shortcomings.

Buy Quality, Consistent Ammunition

Once you start shooting at 300 yards and beyond you’ll develop a deep and personal love affair with quality, consistent cartridges.

Two big things affect why quality ammo is so important:

Bullet weight and shape. Some bullets are shaped to enable more consistent, accurate trajectory than others. A boat-tail round is designed to stay flatter and more on target than one that has a flat tail.

Heavier weight bullets will be more resistant to wind than lighter-weight bullets. With a 5.56/.223 rifle, I’ve found that 75 grains is a solid weight for staying on target in low-to-moderate winds at up to 500 yards.

Consistent loading and velocity. Cheaper ammo will have inconsistency in the amount of powder, and even a small amount of variation will result in one bullet having a slightly higher velocity than another — and thereby shooting higher and being less-wind-affected than the next.

In order to take accurate shots at 300-600 yard distances, you want to have ammo that is consistently loaded so you know where each shot should land, and can make reasonable adjustments when a shot falls short or is affected by wind.

I’ve found that the Hornady Frontier BTHP 75 grain to be consistent and acceptable for shots out to 600 yards. I’ve recently started using Palmetto State Armory’s AAC-brand “Open Tip Match (OTM) 77 grain at a friend’s recommendation. I haven’t been able to test it extensively but seems decent.

I will note here that I disagree with those who say you should only buy and train with one load. For truly close-range shooting and working on the fundamentals at distances of 200 yards and under, I regularly use much cheaper and lighter-weight (55-grain) loads.

And this is blasphemy to some people, but at 2-gun competitions I will often carry a quality light-weight cartridge for the majority of stages at the 50-100 yard distances, and then have a couple magazines loaded with heavier weight loads for mid-range targets. You do have to know that your DOPE will be different, but DOPE doesn’t matter for short-range shots anyway.

Invest in a Simple Magnified Optic

This is the last and final recommendation, and for good reason. Before you invest in a good magnified optic you can learn a lot from shooting off your irons or an unmagnified red-dot.

That being said, you’ll quickly find that without magnification it’s hard to identify a target, make adjustments for elevation and wind, and when necessary, do basic ranging to estimate distance.

There seems to be two camps on mid-range optics:

Spend a lot on a top-quality, first focal-plane scope.

Get the cheapest you can find at Wal-Mart or your local gun store.

I’m here to tell you that there’s a middle way.

For my carbine I wanted an optic that would allow me to quickly take close-range shots for targets at 10-50 yards during 2-gun competitions, but crank up the magnification when needed for longer-range shots.

People will argue on this point, but I find that 6x magnification is sufficient for taking “tactically accurate” shots at 500-600 yards. You won’t be able to place precision shots, but that’s not the use-case for my AR. I want to be able to walk it onto a 18-inch wide steel target at 600 yards, and generally get first-round hits at up to 400 yards.

I’ve been happy with my Burris RT-6 Low Powered Variable Optic (LPVO) as a moderately priced, one-size-addresses-all solution.

I think the glass is higher quality than the other budget offerings, the 1x power allows me to quickly identify targets at close range, while the 6x gives me clarity and a helpful reticle for making wind and elevation adjustments.

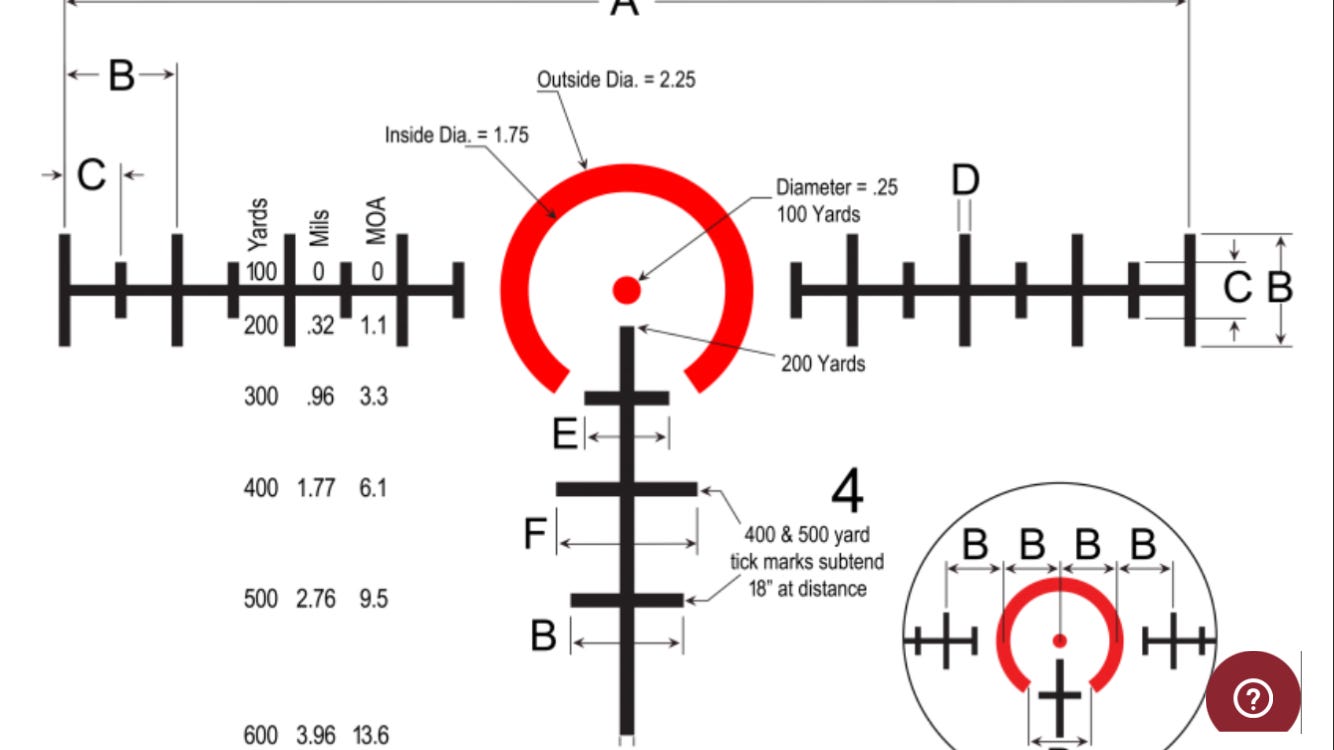

The reticle includes tools for basic ranging, in case you are trying to determine whether a target is at 200 or 400 yards.

At one point I thought my RT-6 having issues holding zero, but it appears that was due to issues with my barrel becoming less consistent after warming up (more on this in a future post).

Conclusion

I’ve learned a lot with my PSA carbine, and built skills using cheaper ammo and a cheaper rifle. I regularly meet guys who want to get into long-range shooting, and I encourage them to start building their skills with the rifle they already own. Certainly, you’ll hit a ceiling at some point. But there’s a lot you can do with that rifle before you get there and spending a lot less money. And that means you can spend more on range time and investing in a quality precision rifle down the road.

I would love to hear about others who started down the path of marksmanship with a low-cost rifle, and what you’ve learned from it. I’ve made some modifications to my PSA homebuild and learned a few things about the tradeoffs with lower-cost options.

More to come in a future post.